Many chess players take a pragmatic approach to the opening: little theory, no complicated lines, clear plans, minimal effort. Lev Polugaevsky chose a different path: he burned with passion for an opening variation where every inaccuracy could be fatal, where one had to master countless lines in great detail, and which had a reputation for being theoretically dubious — the Polugaevsky Variation, one of the sharpest systems in the Najdorf, an opening full of sharp variations. It arises after the moves 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bg5 e6 7.f4 b5!?. At first glance 7…b5 seems to do nothing against White’s threat 8.e5, but White cannot win material here, since after 8.e5 dxe5 9.dxe5 Black plays 9…Qc7, planning 10.exf6 Qe5+ to pick up the unprotected bishop on g5 and remind White of the weaknesses in his position.

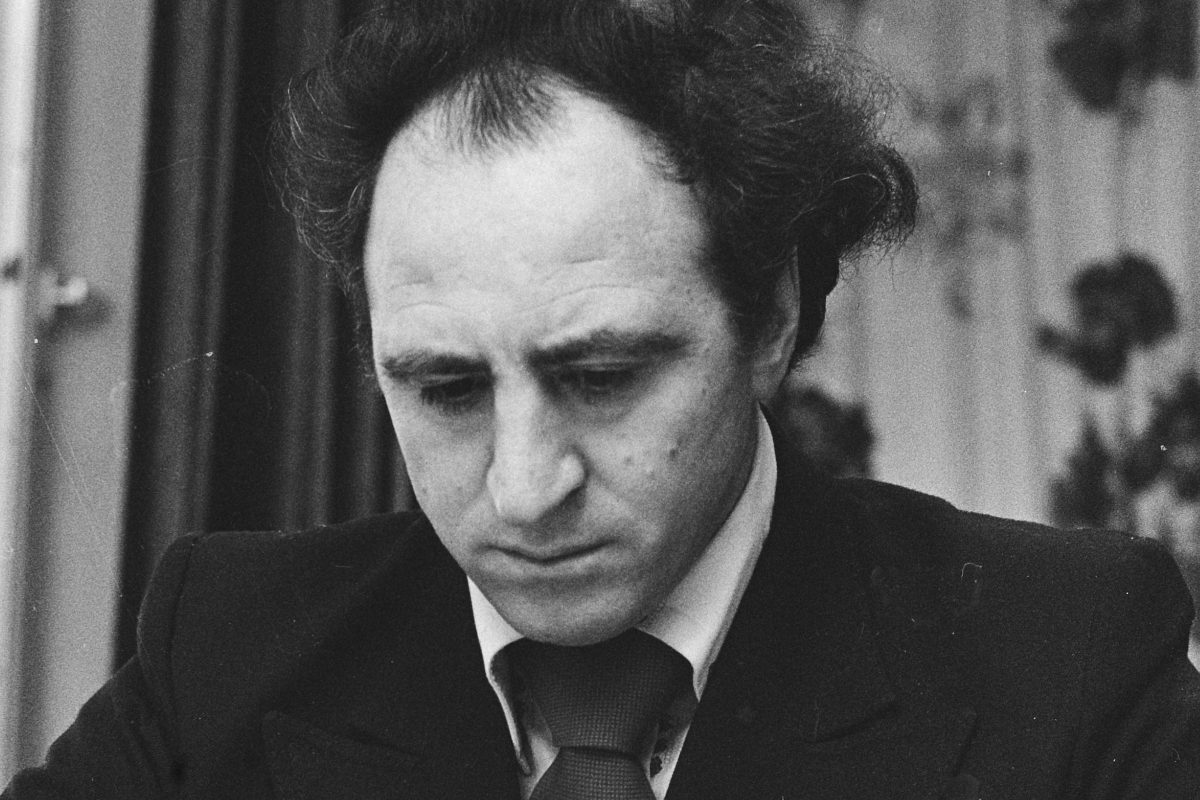

Lev Polugaevsky was born on November 20, 1934, in Mahiljou, in present-day Belarus, and died on August 30, 1995, in Paris from cancer. In the 1970s he was among the best players in the world, reaching as high as third place in the world rankings on two occasions (in July 1972 and again in January 1976). He shared first place three times in the Soviet Championships and qualified three times for the Candidates Matches, though he was eliminated once by Anatoly Karpov (in the 1974 quarterfinals, where Polugaevsky lost clearly by 2.5–5.5) and twice by Viktor Korchnoi (in the 1977 semifinals by 4.5–8.5, and again in the 1980 semifinals by 6.5–7.5).

Polugaevsky was known as a diligent, disciplined, and outstanding theoretician and analyst. He worked as second and trainer for Karpov, and after moving to Paris in 1989 he also coached a number of French talents, among them Joël Lautier. But Polugaevsky’s lasting legacy is his book Grandmaster Preparation, one of the most interesting opening books ever written. Yet it is not a classical opening manual: Polugaevsky does not recommend a repertoire, nor does he provide an overview of the various possibilities for Black and White or the current state of the respective theoretical lines.

Instead, with the help of detailed analyses, he recounts his decades-long passionate devotion to the Polugaevsky Variation and his tireless attempts to prove the theoretical soundness of this line. Polugaevsky’s fascination with the system began between 1956 and 1957, when he first analyzed the move 7…b5 together with the Soviet master Yuri Shaposhnikov, who, like Polugaevsky, lived in the Russian city of Kuibyshev. Over time, Polugaevsky became more and more captivated by the wealth of possibilities for Black.

"Over the course of half a year I spent several hours every day (!) [exclamation mark in the original] at the board with positions from the variation, and when I fell asleep late at night the line would appear in my dreams. … For a time it became, figuratively speaking, my ‘second self’." (Lev Polugaevsky, Grandmaster Preparation, translated here and in the following on the basis of the German edition Aus dem Labor des Großmeisters, Düsseldorf: Rau Verlag 1980, p. 28.)

At the time, however, the move 7…b5 was considered theoretically dubious and hardly playable. Polugaevsky quotes Vasily Smyslov’s reaction to this opening experiment:

“The next milestone in the development of the variation was my game against Bagirov, played in January 1960 at the USSR Championship in Leningrad. When I made my 15th move and got up from the board, Smyslov came over to me and said, in a voice where the reproach was quite unmistakable: ‘Oh, Leo, Leo! What are you allowing yourself at your young age? All your pieces are still sitting on the back rank! Isn’t one game with this variation per championship enough for you? Better spare your nerves!’” (p. 54).

But Polugaevsky had no intention of sparing himself or his nerves — he was determined to remain faithful to his variation:

“Deep inside I was firmly convinced that I would go on playing the line until I came across its definite refutation. And then… I would continue the analysis. I would look for a refutation of the refutation.” (p. 54).

And that is exactly what he did — until the end of his life. The last game Polugaevsky played with “his” variation that can be found in the databases was in 1993, a year before his death, at the PCA tournament in Groningen, where he drew against the young American grandmaster Patrick Wolff. But in the more than thirty years that Polugaevsky lived with his variation, he also went through numerous crises. Perhaps the greatest came at the 29th USSR Championship in 1961 in Baku.

“Hardly had the first rounds of the championship passed when I was handed a note from Judovich. … It contained a precise and detailed analysis showing that in [a critical line of the system] Black was bound to lose. … After all my efforts I was overcome by an ever-growing apathy, and with each passing day the variation meant less and less to me. … So I decided to bid it farewell: ‘That’s enough for me! The endless search and the constant bitter disappointments have made me weary! … Thank you for everything, dear variation! Do not hold my unfaithfulness against me! Farewell forever!’” (pp. 68–70).

After the championship he still played the variation in two more games, but from April 1962 until June 1973 there is not a single game in the databases in which Polugaevsky used the Polugaevsky Variation. Then, while leafing through his old notes, he discovered new possibilities for Black and brought the line back into his repertoire.

It is this ongoing struggle over the playability of his system that makes the book so fascinating. Polugaevsky’s passion is inspiring, and as one reads one can’t help but wonder whether there might not be an opening line that one could study with the same enthusiasm and devotion. At the same time, however, the heretical question arises whether Polugaevsky might not have been even more successful as a player if he had occasionally turned to the Petroff or the Spanish.

But for Polugaevsky it was never just about the points. Thus he writes about a game he played against Zagorovsky in 1959, the “source of the variation”:

“I must confess that I was never as excited in any other game as I was in this one. … I was certain: a new variation had been born. There are moments in life when a person rises above himself, above everything petty and everyday. Such a moment I experienced during the game against Zagorovsky, and it is for that (though not for the point in the tournament table) that I owe the variation eternal gratitude.” (p. 53).

That enthusiasm can still be felt in the game — and throughout the entire book — even decades after its publication.

The German version of this article first appeared in Karl 2/2024. Reprinted with kind permission.

In the first part of the video series, we will look at White’s four main moves: 6. Bg5, 6. Be3, 6. Be2 and 6. Bc4.

Links

.jpg)